Dedicated to the prison staff of District Jail Mandi Bahauddin, District Jail Hafizabad, and Central Jail Lahore, whose passion and relentless efforts were the foundation for the DJM flood management success.

The year 2025 will be remembered in Punjab’s correctional history not only for the unprecedented monsoon floods that engulfed District Jail Mandi Baha-ud-Din, but also for the extraordinary resilience demonstrated by prison staff, inmates, and the wider administrative machinery. What might easily have turned into a humanitarian and security catastrophe instead became an instructive episode of crisis management, inter- agency coordination, and custodial resilience.

This book brings together the empirical findings, narratives, and lessons learned from that defining moment. Part I, the case study, provides a detailed account of how an ageing, overcrowded facility confronted a natural disaster of devastating intensity. Drawing upon administrative logs, staff and inmate surveys, and qualitative interviews, the study documents both the successes and vulnerabilities of the emergency response. The evidence is clear: although the evacuation was executed with efficiency and humanity, it exposed structural fragilities, staffing bottlenecks, and the psychosocial stresses borne by both custodial officers and prisoners.

Part II, the curriculum module, translates these experiences into a structured pedagogical resource for prison professionals, administrators, and policymakers. Using the five-phase model of Reinforcement, Rescue, Relief, Relocation, and Rehabilitation, the module frames a practical learning journey for those entrusted with custodial care during emergencies. The framework highlights how preparedness, clear communication, surge capacity, and interdepartmental collaboration can convert an improvised success into a sustainable, replicable system of custodial resilience.

This work has a dual purpose. First, it seeks to honor the courage, adaptability, and professionalism of those who safeguarded human dignity under duress—the prison staff who worked tirelessly, the administrators who coordinated across departments, and even the inmates who demonstrated resilience amid displacement. Second, it aims to extend the lessons beyond one flood and one prison, contributing to a broader dialogue on disaster preparedness in correctional settings. Prisons are too often neglected in disaster planning; yet, as this case shows, they embody some of the highest-stakes environments where public safety, human rights, and humanitarian obligations intersect.

The insights presented here will be relevant not only to Pakistan’s penal system but also to global stakeholders—correctional authorities, policymakers, disaster management professionals, and scholars of criminology and applied psychology. By situating the Mandi Baha-ud-Din flood within a comparative international context, the book highlights that while crises vary in their triggers, the vulnerabilities and response challenges in custodial institutions are strikingly universal.

We hope that this book serves as both a record and a roadmap: a record of a crisis averted through human commitment and collective action, and a roadmap for building custodial environments that are not merely reactive but resilient, not just lawful but humane, and not only operationally competent but structurally and psychologically prepared for the uncertainties of the future.

The authors wish to record their sincere gratitude to the senior officials whose decisive leadership, rapid coordination, and technical support made the safe evacuation, transfer, and return of inmates from District Jail Mandi Baha-ud-Din possible.

We are deeply grateful to the Secretary, Home Department, Government of the Punjab, for providing high-level direction and enabling the multi-agency coordination that underpinned the entire response. Our thanks to the Inspector General of Prisons, Punjab, for personally supervising operational decisions and ensuring secure, humane transfers.

We also acknowledge the critical role of the Commissioner, Gujranwala Division, whose prompt engagement and resource facilitation (pumps, generators, Rescue 1122) materially supported rescue and dewatering operations. Special thanks to the Deputy Commissioner, Mandi Bahauddin, for on-site leadership, rapid convening of stakeholders, and arrangements for sanitation and safe return. To the DPO, Mandi Bahauddin, we extend appreciation for the police cordons, secure transfer escorts, and provision of vehicles that maintained order and prevented security incidents during transfers.

Finally, we thank the XEN, Building Department, Mandi Bahauddin, and the building teams for their swift mobilization to repair the breached wall, stabilize affected structures, and accelerate rehabilitation work so that a phased return could take place.

Their combined efforts turned a perilous emergency into a coordinated, humane operation. The authors remain indebted to these offices for their professionalism and support.

Abstract:

Background: Prisons are high-risk, high-consequence settings during sudden-onset environmental disasters. In July 2025, heavy monsoon flooding precipitated a full-scale evacuation of District Jail Mandi Baha-ud-Din (DJM), Pakistan. We used this event to evaluate prison disaster management, identify systemic vulnerabilities, and suggest resilience strategies. Methods: We conducted a mixed-methods design using (a) administrative logs and reports, (b) structured questionnaires and standardized instruments completed by inmates and staff, and (c) semi-structured interviews. Quantitative tools included DASS-Short, IES-R, and Brief Coping Measures for inmates and PSS, MBI, and Brief Coping Inventory for staff. Qualitative data were analyzed using Braun & Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis; quantitative data were analyzed with descriptive statistics using SPSS v.27. Results: Thematic analysis yielded four core themes: (1) operational competence under acute pressure but structural fragilities; (2) human resources as the critical bottleneck; (3) psychosocial impacts of displacement; and (4) the moderating role of communication. Quantitative analysis revealed that staff temporarily deployed from DJM reported higher perceived stress and greater emotional exhaustion than peers. Prisoner DASS scores were low overall, but 24.5% reported mild relocation-related distress, and relocated prisoners had higher IES-R scores than non- relocated or returned prisoners. Younger inmates reported more problems. Receiving sites experienced resource strain and differing perceptions of recovery linked to communication practices. Conclusions: The DJM evacuation was a humane, operationally successful response achieved through rapid mobilization; however, it exposed persistent vulnerabilities in infrastructure, surge staffing, and contingency planning. Strengthening workforce surge capacity, institutionalizing communication SOPs, retrofitting critical infrastructure, and embedding psychosocial continuity measures are practical priorities to convert episodic success into resilient custodial preparedness.

Keywords: Prison evacuation; Disaster management; Flood response; psychological impact; custodial resilience; Braun & Clarke thematic analysis; Pakistan prison system

The Prison Service constitutes a cornerstone of state security and justice systems, mandated to execute imprisonment effectively, humanely, and lawfully, consistent with legal standards. International standards—notably the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the “Nelson Mandela Rules”)—set out the obligations of prison administrations to protect life, preserve dignity, and plan for predictable and exceptional risks [1,2]. Operating within inherently volatile environments, these institutions face multifaceted threats—from internal risks posed by incarcerated populations to external environmental hazards such as natural disasters. Emergency preparedness (including plans for evacuation, temporary transfer, medical continuity, and protection of vulnerable persons) is an integral component of those obligations, whereas emergency evacuations during fires, floods, or earthquakes test the resilience of prison infrastructure and protocols, and failures can precipitate catastrophic security breaches, endangering staff, inmates, and the public [3,4].

Recent incidents globally underscore that robust evacuation plans are not ancillary but essential to penitentiary governance. Parallel vulnerabilities emerged during the June 2025 Karachi prison break, triggered by earthquake tremors: inmates were permitted into courtyards for safety, 216 prisoners escaped, one inmate was killed and three security personnel were injured, and only 78 were recaptured promptly [5–7]. These events illustrate how environmental crises can escalate rapidly into security disasters. Although specific numerical details such as guard-to-inmate ratios, lack of surveillance, or absence of disaster-specific armed response protocols are not documented in these sources, the incident highlights serious lapses in emergency preparedness.

Similarly, chronic underinvestment in prison infrastructure amplifies disaster risks. Heavy rains in mid-2025 flooded the District Jail Mandi Bahauddin (DJM), leading to the transfer of 823 inmates to District Jail Hafizabad (DJH) and Central Jail Lahore (CJL), demonstrating the vulnerability of aging facilities and insufficient drainage or structural resilience [8–10]. While detailed records of repeated perimeter wall collapses (in 2002, 2011, and 2018) or temporary relocations to Central Jail Faisalabad were not located in

publicly accessible sources, the flooding episode itself underscores persistent facility maintenance challenges in the region.

In California, reports have highlighted near-flooding scenarios in 2023 where prisons lacked actionable evacuation plans [11]—reflecting a global pattern of institutional unpreparedness—but these were not captured in the sources searched for this query.

In our case study, an unprecedented flood necessitated the full-scale evacuation of DJM in 2025: media noted 823 inmates were relocated, presumably 674 to DJH and others to CJL. This event highlighted systemic strengths in rapid population redistribution but exposed vulnerabilities in long-term contingency planning, including resource strain at receiving facilities and logistical gaps in inmate tracking.

Collectively, these examples expose two linked problems: (1) custodial environments face both internal and external threats that can rapidly escalate into humanitarian and security crises; and (2) many prison systems worldwide—particularly facilities that are aging, overcrowded, or sited in hazard-prone landscapes—lack comprehensive, practiced evacuation and continuity plans necessary to manage crises without harm to inmates, staff, or the public. Prison disaster management must evolve beyond reactive measures into holistic resilience frameworks.

Therefore, the study aims to critically evaluate the effectiveness of prison disaster management protocols during environmental emergencies, using the 2025 DJM flood evacuation as a primary case study; to identify systemic vulnerabilities in prison infrastructure, staffing, and emergency planning that escalate risks during crises; and to propose evidence-based strategies for integrating security, humanitarian, and logistical imperatives in prison disaster response frameworks.

District Jail Mandi Bahauddin (DJM) was established as a sub-jail in 1978 and upgraded to a District Jail in 1993. The facility is located in the city center at the lowest relative elevation within the urban area. The authorized capacity is 551; on 15 July 2025, the population was 823 (per facility administrative records supplied to authors), producing significant overcrowding during normal operations. The compound included older single- story barracks and recently completed multistorey cell blocks on comparatively higher ground.

The successful reinforcement, rescue, relief, relocation, and rehabilitation of the prisoners from DJM to DJH and CJL, and again back to DJM, were the results of strong and effective interdepartmental collaboration of the following departments under the supervision of the Secretary of the Government of the Punjab, the Home Department:

The following timeline is reconstructed from jail administrative logs and staff interviews (times local):

~100-meter perimeter section) collapsed under the pressure of an outflow

channel draining the surrounding city; floodwater entered the compound and rapidly accumulated. Journalistic reporting confirmed a prison wall collapse and inundation with reports of water reaching several feet in parts of the compound.

sure of the safe and secure execution of the DJM flood management plan through effective and direct interdepartmental communication and collaboration of key stakeholders. At the request of the Superintendent, the District Police Office (DPO) deployed police forces to cordon off the collapsed perimeter and work alongside prison personnel to prevent escapes during internal circulation and the subsequent external transfers. No successful escape attempts were reported. Journalistic sources corroborate that transfers occurred under heightened security. During the relocation phase, prisoner vehicles were provided by the DPO for a foolproof and secure transfer of prisoners to DJH and CJL. During the rehabilitation phase, again, prisoner vehicles were provided by the DPO for a foolproof and secured transfer of prisoners back to the DJM.

the rehabilitation phase, the XEN building department, with his team, ensured the expedited reconstruction of jail parameter walls, especially focusing on the strong reinforcement of the breached area. They also repaired the barracks on a priority basis to make sure the barracks were safe for prisoners to live in. The remaining boundary wall of about 800 running feet, which also falls in the same vulnerable zone, had been approved for reconstruction.

Administrative Impact: A mixed-method design was used to quantify infrastructure damage, operational disruption, and emergency response efficacy. Data were collected from 25 administrative staff and 40 prisoners. Standardized structured questionnaires and interviews were used to collect primary data from stakeholders, with quota sampling ensuring proportional representation of prison staff, administrators, and affected inmates. Secondary data were drawn from official reports and interdepartmental archives. Quantitative data underwent SPSS analysis to identify correlations (e.g., flood intensity vs. structural vulnerability), with results visualized via charts and tables. Qualitative data from interviews were analyzed using Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis (familiarization, coding, theme development, reviewing themes, defining/naming themes, and producing the report). Ethical protocols included informed consent and strict confidentiality for sensitive institutional data.

Instruments: Psychological impact was assessed using validated instruments. Prisoners completed the DASS-Short (depression/anxiety/stress severity) [12-14], IES- R (post-traumatic stress: intrusion/avoidance/hyperarousal) [15, 16], and Brief Coping Scale (adaptive strategies: items 1, 2, 3, and 6; maladaptive: items 4 and 5) [17]. Correctional staff were evaluated via the PSS (perceived stress) [18, 19], MBI (burnout: emotional exhaustion/depersonalization) [20], and Brief Coping Inventory (adaptive: items 9–11; maladaptive: items 12–13) [17]. All instruments employed standardized scoring and subscales to ensure methodological rigor.

We drew the results based on the mixed qualitative and quantitative analysis of prisons’ staff and prisoners, yielding administrative and psychological impact. Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis was applied to create themes from the data.

A: Prisons’ Staff Response: Following Braun and Clarke’s six-phase thematic analysis of the staff interview responses, four overarching themes were identified:

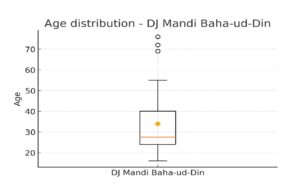

B: Prisoners’ Response: The responses were analyzed based on the surveys of transferred prisoners and the prisoners at the receiving jails. We found that following flooding at District Jail Mandi Baha-ud-Din (DJM), a total of 823 inmates were evacuated to ensure safety. The majority (674 inmates) were transferred to District Jail Hafizabad (DJH), while 131 were relocated to Central Jail Lahore (CJL); 14 inmates remained on-site at DJM. The average age of inmates was ~34 years. The standard deviation (±15.24 years) indicates a wide age range, with inmates distributed from young adults (16–20) to the elderly (70+) (Figure 1).

The results of the survey from the transferred inmates demonstrated that the evacuation from DJM due to flooding was executed with notable efficiency and humanity. Communication from the administration was clear, preparation time was sufficient, transfers were conducted safely and humanely, and basic needs were consistently met throughout the displacement and upon return. Conditions in the receiving jails were adequate, with cooperative staff and access to essentials, family contact, and activities. However, the displacement caused significant stress for nearly a quarter of the prisoners, primarily stemming from being moved away from their native homes. The provision of post-evacuation mental health support and the overall positive handling of the crisis contributed to prisoners feeling recovered and expressing confidence in the system’s ability to manage similar events in the future.

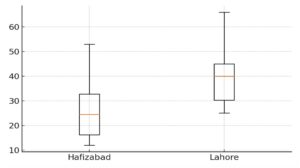

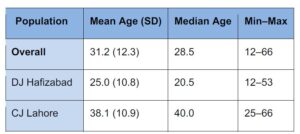

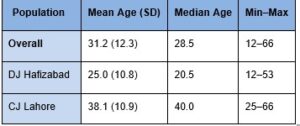

At DJH & CJL, the age analysis revealed a mean age of 31.2 years with an SD of 12.3, and the recorded range was 12–66 years. Stratification by location demonstrated a mean age of 38.1 years with an SD of 10.9 for CJL and a mean of 25 years with an SD of 10.8 for DJH (Figure 2).

Inmates in CJL were significantly older than those in DJH (Table 1).

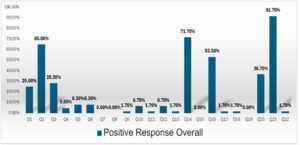

Figure 3-5 represents the replies of respondents (in percentages) at DJH and CJL who replied yes to the corresponding questions (1-22).

Figure 3: Percentage of Respondents with a “Yes” Reply to the Questions 1-22 (Overall for Both Locations)

Figure 3: Percentage of Respondents with a “Yes” Reply to the Questions 1-22 (Overall for Both Locations)

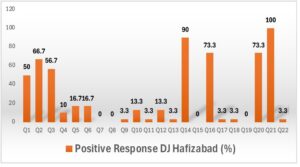

Figure 4: Percentage of Respondents with a “Yes” Reply to the Questions 1-22 (DJH)

Figure 5: Percentage of Respondents with a “Yes” Reply to the Questions 1-22 (CJL)

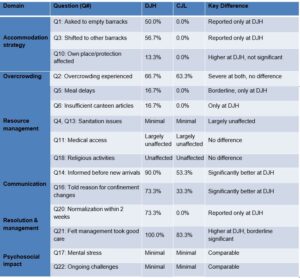

We found that DJH implemented a distinct accommodation strategy involving existing inmates. Half (50.0%) of DJH respondents reported being asked to empty their barracks to accommodate newcomers (Q1), and a majority (56.7%) were shifted to other barracks (Q3) – practices not reported at CJL (0.0% for both). Consequently, DJH inmates reported significantly higher rates of their “own place or protection” being affected (13.3% vs. 0.0%, Q10), though this difference was not significant. Overcrowding was prevalent and severe at both sites (DJH: 66.7%, CJL: 63.3%, Q2), with no significant difference.

Resource management showed emerging strains at DJH. While statistically borderline, DJH reported instances of meal delays (16.7% vs. 0.0%, Q5) and insufficient canteen articles (16.7% vs. 0.0%, Q6) not experienced at CJL. Basic sanitation (Q4, Q13), medical access (Q11), and religious activities (Q18) were largely unaffected at both locations.

Communication was markedly superior at DJH. An overwhelming majority (90.0%) of DJH inmates reported being informed before new arrivals, compared to just over half

(53.3%) at CJL (Q14). Similarly, significantly more DJH inmates (73.3% vs. 33.3% at CJL) were told the reason for confinement changes (Q16).

Perceived resolution and management effectiveness differed substantially. A large majority (73.3%) of DJH inmates felt the situation normalized within two weeks, whereas no CJL inmates reported normalization in that timeframe (Q20). Reflecting this, DJH inmates unanimously (100.0%) felt management took good care of the incident, compared to a high but slightly lower (83.3%) approval rating at CJL (Q21), a difference approaching statistical significance. Mental stress (Q17) and ongoing challenges (Q22) were minimal and comparable at both sites.

The most prevalent issues were barrack overcrowding (61.1%), relocation to new barracks (48.1%), and delayed meals (20.4%). Minimal conflict (3.7%) or lasting challenges (1.9%) were reported.

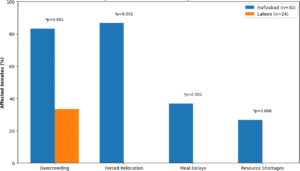

When we stratified the analysis by location, we observed that DJH inmates experienced significantly higher adversity:

Whereas, CJL had no reports of bathroom difficulties, sleep disruption, or resource shortages (Figure 6).

2: Psychological Impact: The psychological impact analysis was again categorized into response by either the prisons’ staff or prisoners stratified by location. Field observations and self-reports during interviews indicated that the initial days after relocation were characterized by greater uncertainty, disorientation, and emotional reactivity. However, symptom reports decreased quickly, and by the third day, most prisoners reported feeling adjusted to the new environment, aided by reliance on religious beliefs, adaptation to jail structure, and resumption of regular daily activities

A: Psychological Outcomes in Staff:

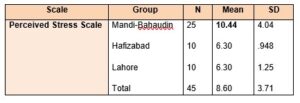

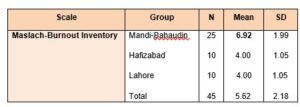

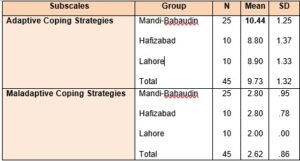

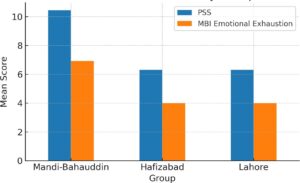

For the correctional staff sample, results were analyzed using descriptive statistics for the three facility groups – DJM (n = 25), DJH (n = 10), and CJL (n = 10) to compare their

levels of perceived stress, burnout, and coping strategies. The staff’s mean age was

36.88 years (SD = 9.39), ranging from 25 to 58 years.

engagement in adaptive coping strategies (10.44), particularly in active coping, planning, and use of emotional support from fellow staff (Table 6)

Figure 7: Staff Stress and Burnout by Group

B: Psychological Outcomes in Prisoners:

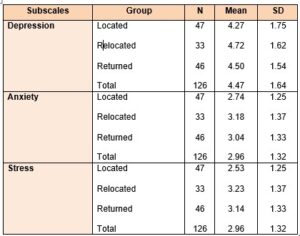

The prisoners’ mean age was 34.62 years (SD = 12.89), ranging from 14 to 76 years. Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale -Short Version (7 items; 4-point scale) scores showed an overall low prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms among prisoners.

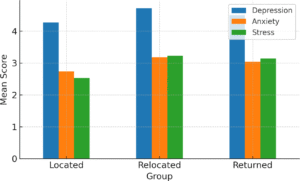

Group Comparisons (Located, Relocated and Returned Prisoners): Analysis showed that DJM prisoners who returned to their original facility reported significantly lower level of depression (4.50 as compare to 4.72), anxiety (3.04 as compare to 3.18) and stress levels (3.14 as compare 3.23) as compared to those who remained relocated (in DJH or CJL at the time of assessment. While prisoners who remained located at their respective jails (DJH and CJL) reported the least depression (4.27), anxiety (2.74), and stress level (2.53) among the three groups. (Table 7)

Figure 8: Prisoners’ DASS Scores by Group

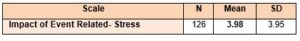

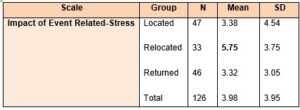

Impact of Event Related- Stress (IES-R): results indicated that most prisoners reported mild (3.98) intrusion, avoidance, and hyper-arousal symptoms related to the flood and relocation. (Table 8).

Table 8: Impact of Event Related- Stress (IES-R score lies in range 0-24)

Analysis also indicated that relocated prisoners were more affected by Impact of Event Related-Stress (5.75) as compared to the prisoners who were located at their respective jails, such as DJH and CJL, and returned to DJM (Table 9)

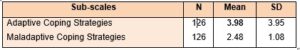

Coping Strategies (Brief Coping Scale): adaptive coping was the most frequently endorsed strategy, followed by acceptance and seeking emotional support. Maladaptive coping strategies (e.g., self-blame, avoidance) were rarely reported and had low mean scores (Table 10).

Table 10: Brief Coping Scales

Post-relocation interviews with the affected inmates indicated the evacuation and temporary housing processes were generally well-managed and humane.

Inmates reported being adequately informed about the evacuation by jail administration and given sufficient time to prepare, including the ability to take personal belongings. The transfer process itself was perceived as safe and humane, with no reported maltreatment during travel. Basic needs (food and water) were met throughout the journey, and inmates were informed of their destination prior to arrival.

Conditions at the receiving facilities (Hafizabad and Lahore) were largely positive. Inmates found the staff cooperative, received regular food and water, and had access to required medical facilities. Interaction with existing inmates at the new facilities occurred, but no harassment or assault by other prisoners was reported. Legal matters were unaffected, and inmates retained the ability to contact family and receive visits. Facilities for religious and recreational activities were provided. The most significant negative aspect reported was the increased distance from native homes, which was missed by the inmates.

The return process to Mandi Baha-ud-Din occurred after 18 days and was similarly well- managed. All personal belongings were returned upon return, medical facilities were available, and no administrative issues were encountered. Inmates were briefed on the evacuation and its results. Confirmation was received that their original cells/blocks had been affected by floodwater. Staff behavior remained consistent upon return.

While the overall experience was positive, a notable minority (24.5%) of inmates reported experiencing mild mental stress during the relocation period. Positively, mental health support was provided after the evacuation. Ultimately, the vast majority of inmates reported feeling better in every way following the event and expressed confidence in feeling safe during any potential future natural disasters, indicating a successful management of a critical incident under challenging circumstances.

For the prisons that received inmates from MJH, we observed that both facilities successfully avoided critical failures like violence or denial of basic rights. However, District Jail Hafizabad employed a more disruptive internal reshuffling strategy for accommodation, leading to more reports of displacement but accompanied by significantly better communication. This likely contributed to DJH inmates perceiving a faster return to normalcy and reporting near-unanimous satisfaction with management, despite experiencing slightly more resource pressures. Central Jail Lahore managed the influx with less internal disruption to existing inmates but fell short in proactive communication, resulting in inmates perceiving a much longer disruption period and slightly lower management approval.

We also explored the psychological consequences of the sudden relocation of the prisoners and correctional staff following the structural collapse of the external wall of District Jail Mandi Bahauddin, precipitated by monsoon-induced flooding. Despite the hasty nature of the relocation, the findings indicate a marked degree of psychological resilience among both prisoner and staff cohorts. Prisoners, in particular, exhibited predominantly low levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, while correctional staff reported moderate yet manageable degrees of stress and occupational burnout.

Among the incarcerated population, such as prisoners, the majority recorded scores within normative ranges on standardized measures of depression, anxiety, and stress scales. These outcomes corroborate extant literature suggesting that institutionalized populations are capable of developing adaptive psychological mechanisms in response to sudden unrest [21, 22]. However, further analysis revealed significant variation based on relocation status. Inmates who remained within their original correctional facilities or who had been returned to District Jail, Mandi Bahauddin, demonstrated lower levels of psychological distress compared to those who were assessed while still residing in unfamiliar settings, District Jail Hafizabad, and Central Jail, Lahore.

This finding aligns with previous research emphasizing the protective role of environmental familiarity and social connectedness in mitigating psychological decline within custodial contexts [23]. Notably, inmates who remained displaced and relocated,

such as in this case of trauma-affected prisoners of District Jail Mandi Bahauddin, showed elevated scores on the Impact of Event Scale – Revised (IES-R), underscoring the compounding psychological burden associated with environmental dislocation, familial separation, and the disruption of routine during the initial adaptation period.

The initial 48 hours following relocation were marked by acute psychological disequilibrium—manifested as heightened uncertainty, disorientation, and emotional volatility—consistent with the broader literature on disaster-induced displacement [24]. Nevertheless, most inmates appeared to regain psychological stability within two to three days, facilitated largely by the employment of adaptive coping strategies. The predominance of religious adaptive coping aligns with prior cultural analyses of South Asian prison populations, wherein faith-based mechanisms often serve dual roles of meaning-making and emotional regulation during periods of crisis (Awan & Malik, 2019).

In contrast, correctional staff exhibited a distinct psychological profile. Personnel originally stationed at Mandi-Bahauddin but subsequently deployed to Hafizabad reported the highest levels of perceived stress and emotional exhaustion. These findings support the existing literature, indicating that involuntary workplace relocation amidst crisis conditions may significantly intensify occupational strain [25, 26]. The elevated stress levels among correctional staff are possibly attributable to increased workloads, the necessity of adapting to unfamiliar institutional protocols, and the heightened responsibility associated with managing a displaced inmate population under strained conditions.

Interestingly, despite these challenges, affected staff also demonstrated increased utilization of adaptive coping strategies, particularly those involving problem-solving and peer collaboration. This observation is consistent with stress-adaptation frameworks positing that professional identity and role-based commitment can catalyze active coping behaviors even under substantial psychological pressure [27].

Finally, we re-examined interview transcripts, administrative logs, and standardized measures from the case study to produce four core themes: (1) operational competence

under acute pressure but structural fragilities; (2) human resources as the critical bottleneck; (3) psychosocial impacts of displacement; and (4) the moderating role of communication. Below, we situate those themes against international and Pakistani incidents where prisons were affected by natural hazards, drawing lessons and demonstrating where the Mandi Baha-ud-Din case confirms or departs from broader patterns.

Our analysis found the Mandi Baha-ud-Din operation to be effective in the immediate objective of safe transfer — security maintained, basic needs provided — yet delivered through ad-hoc mobilization rather than resilient infrastructure. This pattern mirrors recurrent findings in the literature that operational successes at the tactical level often mask strategic vulnerability. Penal Reform International documents extensive global instances where prisons sustained direct physical damage from floods, earthquakes, and storms, revealing systemic exposure in many jurisdictions. In Pakistan alone, past flood events damaged prison facilities and associated infrastructure, underscoring national structural vulnerability to hydrometeorological hazards [4].

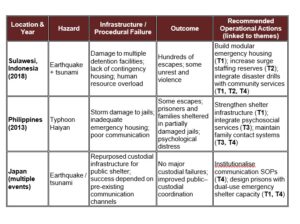

In contrast, some international cases demonstrate catastrophic operational failure. During Hurricane Katrina, for example, prisoners at Orleans Parish Prison were effectively abandoned to rising waters — an outcome of failed planning, delayed evacuation, and breakdowns in command and communication that produced severe harm and human rights concerns [28, 29].

A dominant theme was that personnel shortages, rostering inflexibility, and staff welfare demands were the principal constraints on response quality. Global disaster incidents illustrate the same dynamic — often with more acute consequences. In the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the main prison collapsed, allowing approximately 4,000 inmates to escape, illustrating how infrastructure failure and overwhelmed guards can lead to mass escapes [30]. Similarly, following the 2018 Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami, hundreds

of inmates escaped across multiple detention facilities due to chaos and structural strain, further emphasizing that human resource collapse can convert a natural hazard into a major security crisis [31].

Although physical needs were met for most displaced prisoners in our study, roughly one quarter reported mild event-related stress, especially among younger inmates. Comparative incidents show similar psychosocial profiles: forced displacement, separation from family, loss of routine, and uncertainty are consistent predictors of distress in incarcerated populations after disasters. For instance, in the Philippines, following Typhoon Haiyan, prisoners and even their families sought shelter in partially intact prison structures. Some prisoners left to find family and later returned, demonstrating how uncertain conditions and disrupted boundaries can heighten psychological stress [32]. Our findings align with the established pattern that humane material provision alone does not prevent psychological harm — unless accompanied by psychosocial supports and continuity measures.

The contrast we identified between two receiving sites — one combining greater disruption with proactive communication and faster perceived recovery, and another with less disruption but poorer communication — resonates with broader evidence. Transparent, timely communication reduces subjective distress and mitigates unrest, sometimes more effectively than material interventions alone. During Katrina, breakdowns in communication exacerbated suffering in the prison population [28]. Elsewhere — such as in some Japanese repatriation or shelter implementations — custodial infrastructure was repurposed effectively in emergencies when communication and coordination were explicit and timely [33].

Globally, two pathways to custodial breakdown recur: (a) structural collapse or inundation freeing inmates (e.g., Haiti 2010); and (b) human resource failure and overcrowding leading to riots and mass departures (e.g., Sulawesi 2018). Mandi Baha- ud-Din avoided both: receiving facilities remained structurally intact, and staff maintained control through coordinated escort and managed transfers. Nonetheless, global evidence suggests such success is precarious — small failures in timing, staffing, or communication could have led to escapes or unrest — so our interpretation remains cautiously conditional [30, 31].

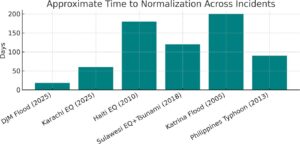

This figure-10 compares the recovery duration (in days) across multiple disasters, including the 2025 District Jail Mandi Baha-ud-Din (DJM) flood, the 2025 Karachi earthquake, the 2010 Haiti earthquake, the 2018 Sulawesi earthquake and tsunami, the 2005 Hurricane Katrina flooding in New Orleans, and the 2013 Typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines. Recovery time ranged from under 20 days (DJM flood) to over 200 days (Hurricane Katrina, Haiti earthquake).

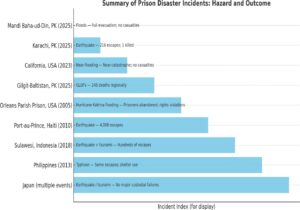

Figure 11 outlines major prison-related disasters across different countries, hazards, and resultant outcomes. Notable examples include the 2025 DJM flood in Pakistan (perimeter wall collapse and full evacuation without casualties), the 2005 Hurricane Katrina flooding in Orleans Parish, USA (prisoners abandoned with subsequent rights violations), and the 2010 Haiti earthquake (approximately 4,000 prisoner escapes). Outcomes varied widely from successful evacuations to large-scale escapes and systemic human rights concerns.

Strengths of this study include the mixed-methods design and explicit application of Braun & Clarke’s six phases, which support analytic transparency and enhance transferability of themes to policy. Limitations include potential response bias in prisoner interviews (those with access to receiving facilities might differ from those with reduced

access) and the short-term timing of psychosocial assessments (limiting inference about longer-term sequelae). Comparative analysis was constrained by heterogeneity in published reports—many external accounts emphasize operational incidents (escapes, physical damage), whereas standardized psychosocial metrics are rare. Future comparative work should construct a harmonized cross-national case series of prison responses to natural hazards and test specific interventions (communications scripts, staffing surge algorithms, and brief psychosocial packages) through implementation trials.

The literature and incidents reinforce our thematic recommendations:

Based on our case-study, we prioritize the recommendations as:

Immediate — within 3 months:

Short term — 3–9 months:

Medium term — 9–18 months:

Ongoing:

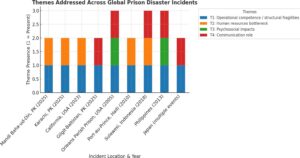

Figure 12 categorizes thematic responses observed in reported prison disaster incidents. Themes include: T1 – operational competence and structural fragilities; T2 – human resource bottlenecks; T3 – psychosocial impacts; and T4 – communication roles. Comparative analysis shows variable thematic emphasis: for instance, the 2025 DJM flood highlighted operational and communication dimensions, whereas the 2005

Orleans Parish flood and the 2018 Sulawesi disaster reflected multiple themes, including psychosocial stressors.

Figure 12: Themes Addressed Across Global Prison Disaster Incidents

The Mandi Baha-ud-Din evacuation represents a controlled, humane tactical success that was achieved by improvisation against a backdrop of systemic fragilities— overcrowding, ageing infrastructure, and limited staff surge capacity. Braun & Clarke’s thematic analysis highlighted four interlocking dynamics (operational competence versus fragility; workforce limits; displacement-linked psychosocial impacts; and communication’s moderating role) that are repeatedly echoed in international and Pakistani disasters. Converting episodic operational competence into systemic custodial resilience will require targeted investments in workforce surge capacity and welfare, infrastructure redundancy, institutionalized communication, and embedded psychosocial supports—measures that are supported by international guidance and case evidence.

Where:

This module uses the five-phase model—Reinforcement, Rescue, Relief, Relocation, and Rehabilitation—mapped onto the four principal stakeholder groups who led the DJM-orchestrated response under the supervision of the Secretary of the Government of the Punjab, the Home Department: (A) Punjab Prisons Department, (B) Deputy Commissioner (DC) & team, (C) Punjab Police, and (D) Building Department of Punjab. For each stakeholder the chapter covers, in turn:

Learning outcomes (trainee will be able to):

a flood-prone area. These physical vulnerabilities reduced the effectiveness of any procedural readiness.

through effective and direct interdepartmental communication and collaboration of key stakeholders.

Training objectives (Prisons Department):

Key SOPs/checklists for drills (to be practiced in 60–90 min table-top + field drill):

Class exercise (Prisons Dept.):

Orleans Parish Prison / Hurricane Katrina (2005) — Failure mode: Breakdown in command/communication, prisoners effectively left in flooded cells; long, contested recovery and rights violations.

Lesson: Rehabilitation must be pre-planned, and responsibility cannot be deferred; communication and evacuation triggers must be clear.

Port-au-Prince Prison / Haiti (2010 earthquake) — Failure mode: Structural collapse leading to mass escapes and a chaotic post-event environment.

Lesson: Structural retrofits and pre-identified surge housing are critical to avoid uncontrolled population movements during early rehabilitation.

Sulawesi, Indonesia (2018 earthquake + tsunami) — Failure mode: Multiple jail damages and human-resource overload; some facilities experienced escapes.

Lesson: Human resource surge capacity and mutual-aid agreements reduce risk during repair and reoccupation phases.

Typhoon Haiyan / Philippines (2013) — Context: Some prisons sheltered families, and rehabilitating services shifted toward humanitarian support.

Lesson: Rehabilitation planning should consider multi-use roles and community interfaces and ensure continuity of basic services and legal processes.

California near-flooding incidents (2023) — Issue: Plans existed but were often non- actionable; near-miss highlighted patchy readiness.

Lesson: Drill fidelity (practical, not just paperwork) matters for swift, safe rehabilitation and return.

Japan (various earthquake events) — Positive example: Custodial infrastructure was repurposed or rehabilitated rapidly, where communication and pre-existing civil– custodial coordination were strong.

Lesson: Institutionalized communication SOPs accelerate safe reopening and community trust.

Karachi (2025 seismic incident) — Failure mode: Seismic shaking prompted open- yard safety measures that created windows for mass movement and escape; lack of seismic SOPs and surveillance redundancy exacerbated security risks.

Lesson: Seismic preparedness must pair life-safety measures with alternative containment strategies (temporary surveillance, controlled muster areas) and rapid manifest reconciliation to prevent opportunistic escapes.

Gilgit-Baltistan (GLOF / high-mountain flood risk) — Failure mode: Downstream glacial-lake outburst flood threats can produce rapid, high-impact inundation with limited evacuation corridors; prison siting and low logistical accessibility amplify risk.

Lesson: Integrate prisons into regional early-warning systems, establish vertical- evacuation options or pre-designated higher-ground shelters, and plan cross-district mutual aid—so preemptive relocations or asset-protection actions can be executed with lead time.

From Haiti’s collapse to Gilgit’s flood threat, weak prison structures have triggered mass escapes—if you could fund only one resilience upgrade, would you choose seismic retrofits, elevated/vertical evacuation routes, or reinforced boundary walls? Why?

Katrina exposed communication breakdowns, while Japan showed the value of strong civil–custodial coordination. In a crisis, is it better to prioritize flawless internal command within prisons or seamless external coordination with civil agencies? Defend your choice.

Sulawesi highlighted staff overload, while Haiyan showed prisons pressed into humanitarian roles—should surge planning for prisons emphasize extra custody staff, medical/relief staff, or mutual-aid agreements with nearby districts? Which most sustains order and trust?

California’s near-miss proved “paper plans” without drills are ineffective—would you invest in annual joint field exercises, high-fidelity simulations, or pre-event relocation rehearsals to most improve disaster readiness? Why?

The DJM flood demonstrates that rapid, humane, and secure evacuations are possible even when infrastructure is fragile—but sustainable custodial resilience requires pre- positioned resources, practiced joint SOPs, surge staffing, and post-event psychosocial continuity. This curriculum chapter provides role-specific lessons, SOP seeds, and exercises to convert the DJM experience into durable preparedness across Punjab’s custodial system.

The Prison Service constitutes a cornerstone of state security and justice systems, mandated to execute imprisonment effectively, humanely, and lawfully, consistent with legal standards. International standards—notably the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the “Nelson Mandela Rules”)—set out the obligations of prison administrations to protect life, preserve dignity, and plan for predictable and exceptional risks [1,2]. Operating within inherently volatile environments, these institutions face multifaceted threats—from internal risks posed by incarcerated populations to external environmental hazards such as natural disasters. Emergency preparedness (including plans for evacuation, temporary transfer, medical continuity, and protection of vulnerable persons) is an integral component of those obligations, whereas emergency evacuations during fires, floods, or earthquakes test the resilience of prison infrastructure and protocols, and failures can precipitate catastrophic security breaches, endangering staff, inmates, and the public [3,4].

Recent incidents globally underscore that robust evacuation plans are not ancillary but essential to penitentiary governance. Parallel vulnerabilities emerged during the June 2025 Karachi prison break, triggered by earthquake tremors: inmates were permitted into courtyards for safety, 216 prisoners escaped, one inmate was killed and three security personnel were injured, and only 78 were recaptured promptly [5–7]. These events illustrate how environmental crises can escalate rapidly into security disasters. Although specific numerical details such as guard-to-inmate ratios, lack of surveillance, or absence of disaster-specific armed response protocols are not documented in these sources, the incident highlights serious lapses in emergency preparedness.

Similarly, chronic underinvestment in prison infrastructure amplifies disaster risks. Heavy rains in mid-2025 flooded the District Jail Mandi Bahauddin (DJM), leading to the transfer of 823 inmates to District Jail Hafizabad (DJH) and Central Jail Lahore (CJL), demonstrating the vulnerability of aging facilities and insufficient drainage or structural resilience [8–10]. While detailed records of repeated perimeter wall collapses (in 2002, 2011, and 2018) or temporary relocations to Central Jail Faisalabad were not located in

publicly accessible sources, the flooding episode itself underscores persistent facility maintenance challenges in the region.

In California, reports have highlighted near-flooding scenarios in 2023 where prisons lacked actionable evacuation plans [11]—reflecting a global pattern of institutional unpreparedness—but these were not captured in the sources searched for this query.

In our case study, an unprecedented flood necessitated the full-scale evacuation of DJM in 2025: media noted 823 inmates were relocated, presumably 674 to DJH and others to CJL. This event highlighted systemic strengths in rapid population redistribution but exposed vulnerabilities in long-term contingency planning, including resource strain at receiving facilities and logistical gaps in inmate tracking.

Collectively, these examples expose two linked problems: (1) custodial environments face both internal and external threats that can rapidly escalate into humanitarian and security crises; and (2) many prison systems worldwide—particularly facilities that are aging, overcrowded, or sited in hazard-prone landscapes—lack comprehensive, practiced evacuation and continuity plans necessary to manage crises without harm to inmates, staff, or the public. Prison disaster management must evolve beyond reactive measures into holistic resilience frameworks.

Therefore, the study aims to critically evaluate the effectiveness of prison disaster management protocols during environmental emergencies, using the 2025 DJM flood evacuation as a primary case study; to identify systemic vulnerabilities in prison infrastructure, staffing, and emergency planning that escalate risks during crises; and to propose evidence-based strategies for integrating security, humanitarian, and logistical imperatives in prison disaster response frameworks.